You know that out of the entire family of Grigory Rasputin, only one of his daughters survived, about whose life I suggest you read further. Quite interesting facts.

Here she is in the picture - in her father's arms. On the left is sister Varvara, on the right is brother Dmitry.

Varya died in Moscow from typhus in 1925, Mitya died in exile in Salekhard. In 1930, he was exiled there along with his mother Paraskeva Fedorovna and his wife Feoktista. My mother did not make it to exile; she died on the way.

Dmitry died of dysentery on December 16, 1933, on the anniversary of his father’s death, outliving his wife and little daughter Lisa by three months.

Varvara Rasputina. Post-revolutionary photo, saved by a friend. Damaged deliberately, out of fear of reprisals from the Soviet government.

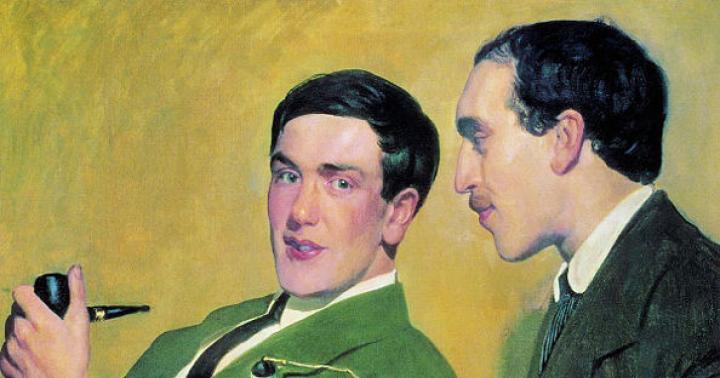

The Rasputin family. In the center is the widow of Grigory Rasputin Paraskeva Feodorovna, on the left is his son Dmitry, on the right is his wife Feoktista Ivanovna. In the background is Ekaterina Ivanovna Pecherkina (a worker in the house).

The frozen body of G. Rasputin, found in Malaya Nevka near the Bolshoi Petrovsky Bridge.

On the night of December 17, 1916, Rasputin was killed at the Yusupov Palace on the Moika. A note was found in his old sheepskin coat (Matryona wrote, according to her father):

“I feel that I will pass away before the first of January. I want to tell the Russian people, Dad, Mom and children what they should do. If I am killed by ordinary murderers and my fellow peasant brothers, then, Tsar of Russia, you will not have to fear for your children. They will reign for many more centuries. But if the nobles destroy me, if they shed my blood, then their hands will be stained with my blood for twenty-five years and they will leave Russia. Brother will rise up against brother. They will hate and kill each other, and there will be no peace in Russia for twenty-five years. Tsar of the Russian land, if you hear the ringing of a bell that tells you that Gregory has been killed, know that one of yours arranged my death, and none of you, none of your children will live more than two years. They will be killed...

I will be killed. I am no longer among the living. Pray! Pray! Be strong. Think about your blessed family!”

In October 1917, shortly before the uprising, Matryona married officer Boris Nikolaevich Solovyov, a participant in the attempt to free Nicholas II during his Siberian exile.

Two girls were born into the family, named after the Grand Duchesses - Tatiana and Maria. The latter was born in exile, where Boris and Matryona fled from Russia.

Prague, Berlin, Paris... The wanderings were long. In 1926, Boris died of tuberculosis and Marochka (as her father affectionately called her) was left with two children in her arms with almost no means of support. The restaurant opened by her husband went bankrupt: poor emigrants often dined there on credit.

Matryona goes to work as a dancer in a cabaret - the dance lessons she took in Berlin from the ballerina of the Imperial Theaters Devillers have finally come in handy.

During one of her performances, the manager of an English circus approached her:

- If you enter a cage with lions, I’ll hire you.

Matryona crossed herself and entered.

They said that one of her famous “Rasputin” looks was enough to stop any predator.

Soon American entrepreneurs became interested in the young tamer, and Matryona, having moved to the United States, began working in the Ringling Bros., Barnum and Bailey Circus, as well as in the Gardner Circus.

She left the arena only after she was once injured by a polar bear. Then all the newspapers started talking about a mystical coincidence: the skin of the bear on which the murdered Rasputin fell was also white.

Later, Matryona worked as a nanny, a nurse in a hospital, gave Russian language lessons, met with journalists, and wrote a large book about her father called “Rasputin. Why?”, which was published several times in Russia.

Matryona Grigorievna died in 1977 in California from a heart attack at the age of 80. Her grandchildren still live in the West. One of the granddaughters, Laurence Io-Solovieva, lives in France, but often visits Russia.

Laurence Huot-Solovieff is the great-granddaughter of G. Rasputin.

I am the daughter of Grigory Efimovich Rasputin.

Baptized by Matryona, my family called me Maria.

Father - Marochka. Now I am 48 years old.

Almost as old as my father was,

when he was taken away from home by a terrible man - Felix Yusupov.

I remember everything and never tried to forget anything

from what happened to me or my family

(no matter how the enemies count on it).

I don't cling to memories like those who do

who are inclined to savor their misfortunes.

I just live by them.

I love my father very much.

Just as much as others hate him.

I can't make others love him.

I don’t strive for this, just as my father did not strive.

Like him, I just want understanding. But, I'm afraid - and this is excessive when it comes to Rasputin.

/From the book "Rasputin. Why?"/

Grigory Rasputin is a well-known and controversial figure in Russian history, debates about which have been going on for a century. His life is filled with a mass of inexplicable events and facts related to his proximity to the emperor’s family and influence on the fate of the Russian Empire. Some historians consider him an immoral charlatan and a fraudster, while others are confident that Rasputin was a real seer and healer, which allowed him to gain influence over the royal family.

Rasputin Grigory Efimovich was born on January 21, 1869 in the family of a simple peasant Efim Yakovlevich and Anna Vasilievna, who lived in the village of Pokrovskoye, Tobolsk province. The day after his birth, the boy was baptized in a church with the name Gregory, which means “awake.”

Grisha became the fourth and only surviving child of his parents - his older brothers and sisters died in infancy due to poor health. At the same time, he was also weak from birth, so he could not play enough with his peers, which became the reason for his isolation and craving for solitude. It was in early childhood that Rasputin felt an attachment to God and religion.

At the same time, he tried to help his father graze cattle, drive a cab, harvest crops and participate in any agricultural work. There was no school in the Pokrovsky village, so Grigory grew up illiterate, like all his fellow villagers, but he stood out among others because of his illness, for which he was considered defective.

At the age of 14, Rasputin became seriously ill and was almost dying, but suddenly his condition began to improve, which, according to him, happened thanks to the Mother of God, who healed him. From that moment, Gregory began to deeply understand the Gospel and, not even knowing how to read, was able to memorize the texts of the prayers. During that period, the gift of foresight awakened in the peasant son, which later prepared for him a dramatic fate.

Monk Grigory Rasputin

Monk Grigory Rasputin At the age of 18, Grigory Rasputin made his first pilgrimage to the Verkhoturye Monastery, but decided not to take a monastic vow, but to continue wandering through the holy places of the world, reaching the Greek Mount Athos and Jerusalem. Then he managed to establish contacts with many monks, wanderers and representatives of the clergy, which in the future historians associated with the political meaning of his activities.

Royal family

The biography of Grigory Rasputin changed its direction in 1903, when he arrived in St. Petersburg, and the palace doors opened before him. At the very beginning of his arrival in the capital Russian Empire The “experienced wanderer” did not even have a means of subsistence, so he turned to the rector of the theological academy, Bishop Sergius, for help. He introduced him to the confessor of the royal family, Archbishop Feofan, who by that time had already heard about Rasputin’s prophetic gift, legends about which were spread throughout the country.

Grigory Efimovich met Emperor Nicholas II during a difficult time for Russia. Then the country was swept by political strikes, revolutionary movements aimed at overthrowing the tsarist government. It was during that period that a simple Siberian peasant managed to make a powerful impression on the tsar, which made Nicholas II want to talk for hours with the wanderer-seer.

Thus, the “elder” acquired colossal influence on imperial family, especially on . Historians are confident that Rasputin’s rapprochement with the imperial family occurred thanks to Gregory’s help in treating his son and heir to the throne, Alexei, who had hemophilia, against which traditional medicine was powerless in those days.

There is a version that Grigory Rasputin was not only a healer for the tsar, but also a chief adviser, as he had the gift of clairvoyance. “The man of God,” as the peasant was called in the royal family, knew how to look into the souls of people and reveal to Emperor Nicholas all the thoughts of the king’s closest associates, who received high positions at the Court only after agreement with Rasputin.

In addition, Grigory Efimovich participated in all government affairs, trying to protect Russia from a world war, which, in his conviction, would bring untold suffering to the people, general discontent and revolution. This was not part of the plans of the instigators of world war, who plotted against the seer, aimed at eliminating Rasputin.

Conspiracy and murder

Before committing the murder of Grigory Rasputin, his opponents tried to destroy him spiritually. He was accused of whipping, witchcraft, drunkenness, and depraved behavior. But Nicholas II did not want to take into account any arguments, since he firmly believed in the elder and continued to discuss all state secrets with him.

Therefore, in 1914, an “anti-Rasputin” conspiracy arose, initiated by the prince, Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich Jr., who later became the commander-in-chief of all military forces of the Russian Empire during the First World War, and Vladimir Purishkevich, who was an actual state councilor at that time.

It was not possible to kill Grigory Rasputin the first time - he was seriously wounded in the village of Pokrovskoye by Khionia Guseva. During that period, while he was on the verge between life and death, Nicholas II decided to participate in the war and announced mobilization. At the same time, he continued to consult with the recovering seer about the correctness of his military actions, which again was not part of the plans of the royal ill-wishers.

Therefore, it was decided to bring the conspiracy against Rasputin to the end. On December 29 (new style), 1916, the elder was invited to the Palace of Prince Yusupov to meet with the famous beauty, the prince’s wife Irina, who needed the healing help of Grigory Efimovich. There they began to treat him to food and drinks poisoned by poison, but potassium cyanide did not kill Rasputin, which forced the conspirators to shoot him.

After several shots in the back, the elder continued to fight for life and was even able to run out into the street, trying to hide from the killers. After a short chase, accompanied by gunfire, the healer fell to the ground and was severely beaten by his pursuers. Then the exhausted and beaten old man was tied up and thrown from the Petrovsky Bridge into the Neva. According to historians, once in the icy water, Rasputin died only a few hours later.

Nicholas II entrusted the investigation into the murder of Grigory Rasputin to the director of the Police Department, Alexei Vasiliev, who got on the “trail” of the killers of the healer. 2.5 months after the death of the elder, Emperor Nicholas II was overthrown from the throne, and the head of the new Provisional Government ordered a hasty end to the investigation into the Rasputin case.

Personal life

The personal life of Grigory Rasputin is as mysterious as his fate. It is known that back in 1900, during a pilgrimage to the holy places of the world, he married a peasant pilgrim like himself, Praskovya Dubrovina, who became his only life partner. Three children were born into the Rasputin family - Matryona, Varvara and Dmitry.

After the murder of Grigory Rasputin, the elder’s wife and children were subjected to repression by the Soviet authorities. They were considered “evil elements” in the country, so in the 1930s the entire peasant farm and the house of Rasputin’s son were nationalized, and the healer’s relatives were arrested by the NKVD and sent to special settlements in the North, after which their trace was completely lost. Only her daughter managed to escape from the hands of the Soviet regime, who emigrated to France after the revolution and then moved to the USA.

Predictions of Grigory Rasputin

Despite the fact that the Soviet authorities considered the elder a charlatan, the predictions of Grigory Rasputin, which he left on 11 pages, were carefully hidden from the public after his death. In his “testament” to Nicholas II, the seer pointed to the completion of several revolutionary coups in the country and warned the tsar about the murder of the entire imperial family “ordered” by the new authorities.

Rasputin also predicted the creation of the USSR and its inevitable collapse. The elder predicted that Russia would defeat Germany in World War II and become a great power. At the same time, he foresaw terrorism at the beginning of the 21st century, which would begin to flourish in the West.

In his predictions, Grigory Efimovich did not ignore the problems of Islam, clearly indicating that in a number of countries Islamic fundamentalism is emerging, which modern world called Wahhabism. Rasputin argued that at the end of the first decade of the 21st century, power in the East, namely in Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, will be captured by Islamic fundamentalists who will declare “jihad” on the United States.

After this, according to Rasputin’s predictions, a serious military conflict will arise, which will last 7 years and will be the last in human history. True, Rasputin predicted one big battle during this conflict, during which at least a million people would die on both sides.

"Rasputin? Of course, he lives over there, three houses away, where the smoke is coming from the chimney."

It wasn’t the most accurate tip, but the grocery store saleswoman in the village of Pokrovskoye didn’t hesitate for a moment when I asked her where the descendant of perhaps the most famous native of Siberia lived. It was here that Grigory Rasputin, the depraved seer and healer who bewitched the Russian imperial family, was born and raised. This is also where Viktor Prolyubshchikov lives, whom the locals simply call “Rasputin.”

I knocked on the door of an old log house, and in response there was a dull grumbling and a suspicious question: “Who’s there?”

When the door opened, a man stood on the threshold, his hair and beard combed rather ostentatiously to resemble the famous “relative”. But the bulging, hypnotic eyes and nose, which Rasputin’s contemporaries described as “as if he had been hit with a shovel,” were absolutely the same.

Grigory Rasputin was killed 100 years ago, in December 1916. He owes his incredible rise - from a peasant hut in remote Siberia to the royal chambers - to the royal family. Especially Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, who sincerely believed that he could cure the heir to the throne, Tsarevich Alexei, who was sick with hemophilia. For the only male heir, even a bloody nose could be fatal.

A hillbilly, a libertine and a drunkard - a close associate of the royal family outraged Russian society. After Russia joined the First world war even the very thought that Rasputin could somehow influence state affairs was unbearable. The authority of the royal family, already low due to constant crises, was completely undermined. According to many, Rasputin put the entire social structure of the empire at risk. One way or another, it was necessary to get rid of him.

Viktor Prolubshchikov makes no secret of his origins. “My great-grandmother was Rasputin’s maid. I think she sinned with him,” he says as we sit at an old wooden table, smoking.

Residents of Pokrovsky differ in their opinions regarding Prolubshchikov’s relationship with Rasputin.

“We pull out strands of his beard for good luck,” says Tatyana Pshenichnikova, the saleswoman who showed me the way to Rasputin’s house. She has no doubt that he is indeed his descendant.

But the owners of the Rasputin Museum, located in the village, are sure that Victor simply looks like him.

I got to Victor in the evening, and my Russian is not good enough for a full interview, so the next day I returned with a translator. Victor was already completely drunk and all attempts to record him on video were unsuccessful. After some unintelligible muttering about healing abilities, I took him at his word and persuaded him to “heal” my back. “It’s in my genes,” he assured.

Theatrically and a little frighteningly, Victor began to move his hands along my spine, muttering something about a demon hiding between my shoulder blades. He clapped his hands and growled, “Get out!” I felt something like lightness after meditation, and Victor, probably exhausted after the “ritual,” collapsed into a chair.

But as soon as the conversation turns to Rasputin’s death, Victor becomes furiously animated: “At first they [Russian nobles] dressed like him, invited him to their dinners, and then suddenly decided to kill him. This is wrong. He was a kind man.”

On the night of December 29 (new style) 1916, Prince Felix Yusupov and his two accomplices, one of whom was Nicholas’s nephew, lured Rasputin to a late dinner, promising that Yusupov’s wife, the beautiful Irina Romanova, would be present. That's the only thing that was accurate. The details of everything that happened after vary. As Yusupov himself said, pies with poison and poisoned wine had no effect on Rasputin, and Yusupov had no choice but to shoot him in the heart.

Rasputin collapsed, but then, like some “Satan in the guise of a peasant,” he jumped to his feet, attacked Yusupov, and then “wheezing and growling” ran out into the street. The conspirators rushed after him and began shooting after him. One of the bullets hit the brain. There is a theory that the British secret services were involved in the murder, but it cannot be documented.

The version of events told by Felix Yusupov has firmly entered the culture - also, however, dubious: there is a high probability that he hoped to make money from his book, and therefore the cold-blooded murder of an unarmed man was overgrown with extraordinary details.

Historians note the similarity of Yusupov's version with Dostoevsky's story "The Mistress". No one will know what happened in the basement of the Yusupov mansion a hundred years ago, but Victor perfectly remembers the most terrible details of this villainous murder.

“They beat him! He’s already lying dead, and they keep beating him!” Victor shook his head. Alcohol and a sense of injustice plunged him into melancholy.

Soon our visit came to an end. Victor somehow had to repay for the “session”. The three of us went to a nearby store, where we spent about $20 on groceries. But Victor remained dissatisfied.

"Where is the vodka?"

Nervous that I'll break the unwritten journalistic rule of not buying a drunk a drink, I try to convince him that the bag in his hands contains good fish and cheese. But the situation only got worse. “No, no, no! I need vodka!” he shouts.

In a rather pitiful tone, I try to explain: “Victor, I’m a journalist. This is not...”

Here he stamps his foot, swinging at us: “I’ll curse you! May you crash on the way home!”

But then the situation was saved by my panicked translator. “I’m not a journalist,” she said as she ran back to the store. Having received his half-liter, Victor brightened up, squeezed my hand as a sign of reconciliation and, saying goodbye, wandered home.

In the minds of most people, Grigory Rasputin is either a magician, sorcerer and sectarian, or a swindler and charlatan, who subjugated the family of the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II to his influence and suffered martyrdom from the conspirators for this. What else do we know about him? Meanwhile, the “holy devil,” as he was called, had a completely normal family - a wife and children...

Family life and wandering

At the age of 19 in Alabatsk, at a church holiday, Gregory met beautiful girl Praskovya Dubrovina and married her. They had a child. However, the firstborn soon died. The death of the baby shocked Gregory so much that he lost faith in God, began going to taverns and even took up robbery... In 1892, a village meeting sentenced him to deportation for a year. Having repented, Gregory went to the Verkhoturyevo Monastery, where he learned to read and write, the law of God and other sciences from the elder hermit Macarius. He also advised him to wander. In 1893, together with his friend Dmitry Pechorkin, Gregory went to Greece, where he visited Orthodox monasteries in the mountains of Macedonia. Then, upon returning to Russia, he visited the Kiev Pechersk Lavra, Solovki, Valaam, Optina Monastery, Nilov Monastery and other holy places. Meanwhile, every summer he visited his wife Praskovya. They had more children: in 1895 - Dmitry, in 1898 - Matryona, in 1900 - Varvara.

Petersburg

In 1905, in the Kiev monastery of St. Michael, Gregory met Grand Duchess Anastasia. She persuaded Rasputin to come to St. Petersburg to help Tsarevich Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia.

The “elder” (as Rasputin was called) treated the prince with herbs, prayers and the laying on of hands. After the “old man’s” treatment, the boy noticeably improved, and Rasputin settled down at court. He acquired enormous influence over the imperial family, which, naturally, did not please the courtiers. They began to spread monstrous rumors about the royal favorite - that he organized orgies, kept a harem of concubines in his house... How true all this was is unknown.

In 1910, his daughters Matryona and Varvara moved to Rasputin’s apartment on Gorokhovaya in St. Petersburg. Their father arranged for them to study at the gymnasium. His wife Praskovya and son Dmitry remained in Pokrovskoye, where the head of the family sometimes visited.

Unlucky fate

After the murder of Rasputin, initiated by Prince Felix Yusupov, the family of the “elder” had a hard time. Son Dmitry married Feoktista Pecherkina in 1918. Until 1930, he and his family lived in Pokrovskoye, then they were “dispossessed” and sent into exile as “evil elements” in Obdorsk (Salekhard). Praskovya Feodorovna died along the way, and three years later Dmitry Feoktist’s wife also died of tuberculosis. Their little daughter Lisa also died. Three months later, dysentery claimed the life of Dmitry Grigorievich. It happened on December 16, 1933, just on the anniversary of my father’s death...

Rasputin's youngest daughter Varvara never married and died in Moscow in 1925, suffering from both typhoid and tuberculosis.

Matryona - lion tamer

The fate of Matryona's eldest daughter, as her father called her, Marochka (she herself preferred to call herself Maria), was much more successful. Literally a few days before the October Uprising of 1917, she married officer Boris Nikolaevich Solovyov, the son of the Holy Synod official Nikolai Vasilyevich Solovyov, who during his lifetime was a close acquaintance of Rasputin. Boris participated in the attempt to free Nicholas II during the royal family's stay in Siberian exile. From this marriage two daughters were born, named after the murdered grand duchesses - Tatiana and Maria. The youngest is already in exile.

The family lived in Romania, the Czech Republic, Germany, France... In Paris, Boris opened a restaurant for Russian emigrants, but soon went bankrupt, as he often fed his compatriots for free... In 1926, Soloviev died of tuberculosis, and his widow was forced to look for a livelihood. At first she went to work as a dancer in a cabaret. Once the manager of an English circus approached her and offered to hire her as a trainer if she could enter a cage with lions. Matryona agreed. She crossed herself and entered the cage with the predators. They didn’t touch her - perhaps thanks to the special “magnetic” look inherited from her father... So “Marie Rasputin, the daughter of a mad monk, famous for her exploits in Russia!” appeared on the posters!

Matryona began touring around the world.

In the late 30s, American entrepreneurs became interested in her. Soon she moved permanently to the United States, working in the Ringling Bros., Barnum and Bailey circuses, as well as in the Gardner circus.

In 1940, Matryona remarried the Russian emigrant Grigory Bernadsky, whom she knew back in Russia. But the marriage lasted only five years.

After she was once injured in the arena by a polar bear, Rasputin's daughter left her circus career. She worked as a nanny, governess, and nurse in a hospital, gave Russian language lessons... Finally, she published a book about her father, “Rasputin. Why? ”, in which in every possible way whitewashed the personality of Rasputin and rejected the accusations attributed to him. “I love my father very much,” she wrote. “Just as much as others hate him.”

Matryona Grigorievna, née Rasputina, having received American citizenship in 1945, worked as a riveter in defense shipyards until her retirement and died in 1977 in California from a heart attack. She was the only one of Rasputin's children to live to old age.

By the way, one of Matryona’s daughters, Maria, was married to a Dutch diplomat, and in the late 40s, their family met the daughter of Prince and Princess Yusupov, Irina, in Greece. Their children - Serge and Ksenia - played together, not suspecting that the grandfather of one became the murderer of the great-grandfather of the other...

One of Rasputin’s great-granddaughters, Laurence Io-Solovieva, lives in France, but often visits Russia. She also visited Pokrovskoye, the homeland of her famous ancestor.

Grigory Efimovich Rasputin (Novykh). Born January 9 (21), 1869 - killed December 17 (30), 1916. Peasant of the village of Pokrovskoye, Tobolsk province. He gained worldwide fame due to the fact that he was a friend of the family of Russian Emperor Nicholas II.

In the 1900s, among certain circles of St. Petersburg society he had a reputation as a “royal friend,” “elder,” seer and healer. The negative image of Rasputin was used in revolutionary and later Soviet propaganda; there are still many rumors about Rasputin and his influence on the fate of the Russian Empire.

The ancestor of the Rasputin family was “Izosim Fedorov’s son.” The census book of the peasants of the village of Pokrovsky for 1662 says that he and his wife and three sons - Semyon, Nason and Yevsey - came to Pokrovskaya Sloboda twenty years earlier from the Yarensky district and “set up arable land.” Nason's son later received the nickname "Rosputa". From him came all the Rosputins, who became Rasputins at the beginning of the 19th century.

According to the yard census of 1858, there were more than thirty peasants in Pokrovskoye who bore the surname “Rasputins,” including Efim, Gregory’s father. The surname comes from the words “crossroads”, “thaw”, “crossroads”.

Grigory Rasputin was born on January 9 (21), 1869 in the village of Pokrovsky, Tyumen district, Tobolsk province, into the family of coachman Efim Yakovlevich Rasputin (1841-1916) and Anna Vasilievna (1839-1906) (nee Parshukova).

Information about Rasputin's date of birth is extremely contradictory. Sources give various dates of birth between 1864 and 1872. Historian K.F. Shatsillo, in an article about Rasputin in the TSB, reports that he was born in 1864-1865. Rasputin himself in his mature years did not add clarity, reporting conflicting information about his date of birth. According to biographers, he was inclined to exaggerate his true age in order to better fit the image of an “old man.”

At the same time, in the metric book of the Slobodo-Pokrovskaya Mother of God Church of the Tyumen district of the Tobolsk province, in part one “About those born” there is a birth record on January 9, 1869 and an explanation: “Efim Yakovlevich Rasputin and his wife Anna Vasilievna of the Orthodox religion had a son, Gregory.” He was baptized on January 10. The godfathers (godparents) were uncle Matfei Yakovlevich Rasputin and the girl Agafya Ivanovna Alemasova. The baby received his name according to the existing tradition of naming the child after the saint on whose day he was born or baptized.

The day of the baptism of Grigory Rasputin is January 10, the day of celebration of the memory of St. Gregory of Nyssa.

I was sick a lot when I was young. After a pilgrimage to the Verkhoturye Monastery, he turned to religion.

Grigory Rasputin's height: 193 centimeters.

In 1893, he traveled to the holy places of Russia, visited Mount Athos in Greece, and then to Jerusalem. I met and made contacts with many representatives of the clergy, monks, and wanderers.

In 1900 he set off on a new journey to Kyiv. On the way back, he lived in Kazan for quite a long time, where he met Father Mikhail, who was associated with the Kazan Theological Academy.

In 1903, he came to St. Petersburg to visit the rector of the Theological Academy, Bishop Sergius (Stragorodsky). At the same time, the inspector of the St. Petersburg Theological Academy, Archimandrite Feofan (Bistrov), met Rasputin, introducing him also to Bishop Hermogenes (Dolganov).

By 1904, Rasputin had acquired the fame of an “old man”, “fool” and “fool” from part of high society society. God's man", which "consolidated the position of a “saint” in the eyes of the St. Petersburg world,” or at least he was considered a “great ascetic.”

Father Feofan told about the “wanderer” to the daughters of the Montenegrin prince (later king) Nikolai Njegosh - Militsa and Anastasia. The sisters told the empress about the new religious celebrity. Several years passed before he began to clearly stand out among the crowd of “God’s men.”

On November 1 (Tuesday) 1905, Rasputin’s first personal meeting with the emperor took place. This event was honored with an entry in the diary of Nicholas II. The mentions of Rasputin do not end there.

Rasputin gained influence on the imperial family and, above all, on Alexandra Feodorovna by helping her son, heir to the throne Alexei, fight hemophilia, a disease against which medicine was powerless.

In December 1906, Rasputin submitted a petition to the highest name to change his surname to Rasputin-Novykh, citing the fact that many of his fellow villagers have the same last name, which could lead to misunderstandings. The request was granted.

Grigory Rasputin. Healer at the throne

Accusation of "Khlysty" (1903)

In 1903, his first persecution by the church began: the Tobolsk Consistory received a report from the local priest Pyotr Ostroumov that Rasputin was behaving strangely with women who came to him “from St. Petersburg itself,” about their “passions from which he relieves them... in the bathhouse”, that in his youth Rasputin “from his life in the factories of the Perm province brought acquaintance with the teachings of the Khlyst heresy.”

An investigator was sent to Pokrovskoye, but he did not find anything discrediting, and the case was archived.

On September 6, 1907, based on a denunciation from 1903, the Tobolsk Consistory opened a case against Rasputin, who was accused of spreading false teachings similar to Khlyst’s and forming a society of followers of his false teachings.

The initial investigation was carried out by priest Nikodim Glukhovetsky. Based on the collected facts, Archpriest Dmitry Smirnov, a member of the Tobolsk Consistory, prepared a report to Bishop Anthony with the attachment of a review of the case under consideration by sect specialist D. M. Berezkin, inspector of the Tobolsk Theological Seminary.

D. M. Berezkin noted in his review of the conduct of the case that the investigation was carried out “persons who have little knowledge of Khlystyism” that only Rasputin’s two-story residential house was searched, although it is known that the place where the zeal is taking place “is never placed in residential premises... but is always located in the backyard - in bathhouses, in sheds, in basements... and even in dungeons... The paintings and icons found in the house are not described, yet they usually contain the solution to the heresy ».

After which Bishop Anthony of Tobolsk decided to conduct a further investigation into the case, entrusting it to an experienced anti-sectarian missionary.

As a result, the case “fell apart” and was approved as completed by Anthony (Karzhavin) on May 7, 1908.

Subsequently, the Chairman of the State Duma Rodzianko, who took the file from the Synod, said that it soon disappeared, but then “The case of the Tobolsk spiritual consistory about the Khlystyism of Grigory Rasputin” in the end it was found in the Tyumen archive.

In 1909, the police were going to expel Rasputin from St. Petersburg, but Rasputin got ahead of them and went home to the village of Pokrovskoye for some time.

In 1910, his daughters moved to St. Petersburg to live with Rasputin, whom he arranged to study at the gymnasium. At the direction of the Prime Minister, Rasputin was placed under surveillance for several days.

At the beginning of 1911, Bishop Feofan suggested that the Holy Synod officially express displeasure to Empress Alexandra Feodorovna in connection with Rasputin’s behavior, and a member of the Holy Synod, Metropolitan Anthony (Vadkovsky), reported to Nicholas II about the negative influence of Rasputin.

On December 16, 1911, Rasputin had a clash with Bishop Hermogenes and Hieromonk Iliodor. Bishop Hermogenes, acting in alliance with Hieromonk Iliodor (Trufanov), invited Rasputin to his courtyard; on Vasilievsky Island, in the presence of Iliodor, he “convicted” him, striking him several times with a cross. An argument ensued between them, and then a fight.

In 1911, Rasputin voluntarily left the capital and made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

By order of the Minister of Internal Affairs Makarov on January 23, 1912, Rasputin was again placed under surveillance, which continued until his death.

The second case of “Khlysty” (1912)

In January 1912, the Duma announced its attitude towards Rasputin, and in February 1912, Nicholas II ordered V.K. Sabler to resume the case of the Holy Synod, the case of Rasputin’s “Khlysty” and transfer it to Rodzianko for the report, “and the palace commandant Dedyulin and transferred to him the Case of the Tobolsk Spiritual Consistory, which contained the beginning of Investigative Proceedings regarding the accusation of Rasputin of belonging to the Khlyst sect.”

On February 26, 1912, at an audience, Rodzianko suggested that the tsar expel the peasant forever. Archbishop Anthony (Khrapovitsky) openly wrote that Rasputin is a whip and is participating in zeal.

The new (who replaced Eusebius (Grozdov)) Tobolsk Bishop Alexy (Molchanov) personally took up this case, studied the materials, requested information from the clergy of the Intercession Church, and repeatedly talked with Rasputin himself. Based on the results of this new investigation, the conclusion of the Tobolsk Church was prepared and approved on November 29, 1912 spiritual consistory, sent to many high-ranking officials and some deputies of the State Duma. In conclusion, Rasputin-Novy was called “a Christian, a spiritually minded person who seeks the truth of Christ.” results of a new investigation.

Rasputin's prophecies

During his lifetime, Rasputin published two books: “The Life of an Experienced Wanderer” (1907) and “My Thoughts and Reflections” (1915).

In his prophecies, Rasputin speaks of “God’s punishment,” “bitter water,” “tears of the sun,” “poisonous rains” “until the end of our century.”

Deserts will advance, and the earth will be inhabited by monsters that will not be people or animals. Thanks to “human alchemy”, flying frogs, kite butterflies, crawling bees, huge mice and equally huge ants will appear, as well as the monster “kobaka”. Two princes from the West and the East will challenge the right to world domination. They will have a battle in land of four demons, but the western prince Grayug will defeat his eastern enemy Blizzard, but he himself will fall. After these misfortunes, people will again turn to God and enter “earthly paradise.”

The most famous was the prediction of the death of the Imperial House: "As long as I live, the dynasty will live".

Some authors believe that Rasputin is mentioned in Alexandra Feodorovna’s letters to Nicholas II. In the letters themselves, Rasputin’s surname is not mentioned, but some authors believe that Rasputin in the letters is designated by the words “Friend”, or “He” in capital letters, although this has no documentary evidence. The letters were published in the USSR by 1927, and in the Berlin publishing house Slovo in 1922.

The correspondence was preserved in the State Archive of the Russian Federation - Novoromanovsky Archive.

Grigory Rasputin with the Empress and the Tsar's children

In 1912, Rasputin dissuaded the emperor from intervening in the Balkan War, which delayed the start of the First World War by 2 years.

In 1915, anticipating the February Revolution, Rasputin demanded an improvement in the capital's supply of bread.

In 1916, Rasputin spoke out strongly in favor of Russia's withdrawal from the war, concluding peace with Germany, renouncing rights to Poland and the Baltic states, and also against the Russian-British alliance.

Press campaign against Rasputin

In 1910, the writer Mikhail Novoselov published several critical articles about Rasputin in Moskovskie Vedomosti (No. 49 - “Spiritual guest performer Grigory Rasputin”, No. 72 - “Something else about Grigory Rasputin”).

In 1912, Novoselov published in his publishing house the brochure “Grigory Rasputin and Mystical Debauchery,” which accused Rasputin of being a Khlysty and criticized the highest church hierarchy. The brochure was banned and confiscated from the printing house. The newspaper "Voice of Moscow" was fined for publishing excerpts from it.

After that in State Duma followed by a request to the Ministry of Internal Affairs about the legality of punishing the editors of Voice of Moscow and Novoye Vremya.

Also in 1912, Rasputin’s acquaintance, former hieromonk Iliodor, began distributing several scandalous letters from Empress Alexandra Feodorovna and the Grand Duchesses to Rasputin.

Copies printed on a hectograph circulated around St. Petersburg. Most researchers consider these letters to be fakes. Later, Iliodor, on advice, wrote a libelous book “Holy Devil” about Rasputin, which was published in 1917 during the revolution.

In 1913-1914 the Masonic Supreme Council VVNR attempted to launch a propaganda campaign regarding Rasputin's role at court.

Somewhat later, the Council made an attempt to publish a brochure directed against Rasputin, and when this attempt failed (the brochure was delayed by censorship), the Council took steps to distribute this brochure in a typed copy.

Assassination attempt by Khionia Guseva on Rasputin

In 1914, an anti-Rasputin conspiracy matured, headed by Nikolai Nikolaevich and Rodzianko.

On June 29 (July 12), 1914, an attempt was made on Rasputin in the village of Pokrovskoye. He was stabbed in the stomach and seriously wounded by Khionia Guseva, who came from Tsaritsyn.

Rasputin testified that he suspected Iliodor of organizing the assassination attempt, but could not provide any evidence of this.

On July 3, Rasputin was transported by ship to Tyumen for treatment. Rasputin remained in the Tyumen hospital until August 17, 1914. The investigation into the assassination attempt lasted about a year.

Guseva was declared mentally ill in July 1915 and released from criminal liability, being placed in a psychiatric hospital in Tomsk. On March 27, 1917, on the personal orders of A.F. Kerensky, Guseva was released.

Murder of Rasputin

Rasputin was killed on the night of December 17, 1916 (December 30, new style) in the Yusupov Palace on the Moika. Conspirators: F. F. Yusupov, V. M. Purishkevich, Grand Duke Dmitry Pavlovich, British intelligence officer MI6 Oswald Rayner.

Information about the murder is contradictory, it was confused both by the killers themselves and by the pressure on the investigation by the Russian imperial and British authorities.

Yusupov changed his testimony several times: in the St. Petersburg police on December 18, 1916, in exile in Crimea in 1917, in a book in 1927, sworn to in 1934 and in 1965.

Starting from naming the wrong color of the clothes that Rasputin was wearing according to the killers and in which he was found, to how many and where bullets were fired.

For example, forensic experts found three wounds, each of which was fatal: to the head, liver and kidney. (According to British researchers who studied the photo, the shot to the forehead was made from a British Webley 455 revolver.)

After a shot in the liver, a person can live no more than 20 minutes and is not able, as the killers said, to run down the street in half an hour or an hour. There was also no shot to the heart, which the killers unanimously claimed.

Rasputin was first lured into the basement, treated to red wine and a pie poisoned with potassium cyanide. Yusupov went upstairs and, returning, shot him in the back, causing him to fall. The conspirators went outside. Yusupov, who returned to get the cloak, checked the body; suddenly Rasputin woke up and tried to strangle the killer.

The conspirators who ran in at that moment began to shoot at Rasputin. As they approached, they were surprised that he was still alive and began to beat him. According to the killers, the poisoned and shot Rasputin came to his senses, got out of the basement and tried to climb over the high wall of the garden, but was caught by the killers, who heard a dog barking. Then he was tied with ropes hand and foot (according to Purishkevich, first wrapped in blue cloth), taken by car to a pre-selected place near Kamenny Island and thrown from the bridge into the Neva polynya in such a way that the body ended up under the ice. However, according to the investigation, the discovered corpse was dressed in a fur coat, there was no fabric or ropes.

The corpse of Grigory Rasputin

The investigation into the murder of Rasputin, led by the director of the Police Department A.T. Vasilyev, progressed quite quickly. Already the first interrogations of Rasputin’s family members and servants showed that on the night of the murder, Rasputin went to visit Prince Yusupov. Policeman Vlasyuk, who was on duty on the night of December 16-17 on the street not far from the Yusupov Palace, testified that he heard several shots at night. During a search in the courtyard of the Yusupovs' house, traces of blood were found.

On the afternoon of December 17, passers-by noticed blood stains on the parapet of the Petrovsky Bridge. After exploration by divers of the Neva, Rasputin’s body was discovered in this place. The forensic medical examination was entrusted to the famous professor of the Military Medical Academy D. P. Kosorotov. The original autopsy report has not been preserved; the cause of death can only be speculated.

Conclusion of the forensic expert Professor D.N. Kosorotova:

“During the autopsy, very numerous injuries were found, many of which were inflicted posthumously. The entire right side of the head was crushed and flattened due to the bruise of the corpse when it fell from the bridge. Death resulted from profuse bleeding due to a gunshot wound to the stomach. The shot was fired, in my opinion, almost point-blank, from left to right, through the stomach and liver, with the latter being fragmented in the right half. The bleeding was very profuse. The corpse also had a gunshot wound in the back, in the spinal area, with a crushed right kidney, and another point-blank wound in the forehead, probably of someone who was already dying or had died. The chest organs were intact and were examined superficially, but there were no signs of death by drowning. The lungs were not distended and there was no water or foamy fluid in the airways. Rasputin was thrown into the water already dead.”

No poison was found in Rasputin's stomach. Possible explanations for this are that the cyanide in the cakes has been neutralized by sugar or high temperature when cooking in the oven.

His daughter reports that after Guseva’s assassination attempt, Rasputin suffered increased acidity and avoided sweet foods. It is reported that he was poisoned with a dose capable of killing 5 people.

Some modern researchers suggest that there was no poison - this is a lie to confuse the investigation.

There are a number of nuances in determining the involvement of O. Reiner. At that time, there were two British MI6 intelligence officers serving in St. Petersburg who could have committed the murder: Yusupov’s friend from University College (Oxford) Oswald Rayner and Captain Stephen Alley, who was born in the Yusupov Palace. The former was suspected, and Tsar Nicholas II directly mentioned that the killer was Yusupov's college friend.

Rayner was awarded an OBE in 1919 and destroyed his papers before his death in 1961.

In Compton's driver's log, there are entries that a week before the murder he brought Oswald to Yusupov (and to another officer, Captain John Scale), and the last time - on the day of the murder. Compton also directly hinted at Rayner, saying that the killer was a lawyer and was born in the same city as him.

There is a letter from Alley written to Scale on January 7, 1917, eight days after the murder: "Although not everything went according to plan, our goal was achieved... Reiner is covering his tracks and will undoubtedly contact you...". According to modern British researchers, the order to three British agents (Rayner, Alley and Scale) to eliminate Rasputin came from Mansfield Smith-Cumming (the first director of MI6).

The investigation lasted two and a half months until the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II on March 2, 1917. On this day, Kerensky became Minister of Justice in the Provisional Government. On March 4, 1917, he ordered a hasty termination of the investigation, while investigator A.T. Vasiliev was arrested and transported to the Peter and Paul Fortress, where he was interrogated by the Extraordinary Commission of Investigation until September, and later emigrated.

In 2004, the BBC aired a documentary "Who killed Rasputin?", brought new attention to the murder investigation. According to the version shown in the film, the “glory” and the idea of this murder belong to Great Britain, the Russian conspirators were only the perpetrators, the control shot to the forehead was fired from the British officers’ Webley 455 revolver.

Who killed Grigory Rasputin

According to the researchers who published the books, Rasputin was killed with the active participation of the British intelligence service Mi-6; the killers confused the investigation in order to hide the British trail. The motive for the conspiracy was the following: Great Britain feared Rasputin's influence on Russian empress, which threatened to conclude a separate peace with Germany. To eliminate the threat, the conspiracy against Rasputin that was brewing in Russia was used.

Rasputin's funeral service was conducted by Bishop Isidor (Kolokolov), who was well acquainted with him. In his memoirs, A.I. Spiridovich recalls that Bishop Isidore celebrated the funeral mass (which he had no right to do).

At first they wanted to bury the murdered man in his homeland, in the village of Pokrovskoye. But due to the danger of possible unrest in connection with sending the body across half the country, they buried it in the Alexander Park of Tsarskoe Selo on the territory of the Church of Seraphim of Sarov, which was being built by Anna Vyrubova.

M.V. Rodzianko writes that in the Duma during the celebrations there were rumors about Rasputin’s return to St. Petersburg. In January 1917, Mikhail Vladimirovich received a paper with many signatures from Tsaritsyn with a message that Rasputin was visiting V.K. Sabler, that the Tsaritsyn people knew about Rasputin’s arrival in the capital.

After February Revolution Rasputin's burial was found, and Kerensky ordered Kornilov to organize the destruction of the body. For several days the coffin with the remains stood in a special carriage. Rasputin's body was burned on the night of March 11 in the furnace of the steam boiler of the Polytechnic Institute. An official act on the burning of Rasputin's corpse was drawn up.

Personal life of Grigory Rasputin:

In 1890 he married Praskovya Fedorovna Dubrovina, a fellow pilgrim-peasant, who bore him three children: Matryona, Varvara and Dimitri.

Grigory Rasputin with his children

In 1914, Rasputin settled in an apartment at 64 Gorokhovaya Street in St. Petersburg.

Various dark rumors quickly began to spread around St. Petersburg about this apartment, saying that Rasputin had turned it into a brothel and was using it to hold his “orgies.” Some said that Rasputin maintains a permanent “harem” there, while others say he collects them from time to time. There was a rumor that the apartment on Gorokhovaya was used for witchcraft, etc.

From the testimony of Tatyana Leonidovna Grigorova-Rudykovskaya:

"...One day Aunt Ag. Fed. Hartmann (mother's sister) asked me if I wanted to see Rasputin closer. ... Having received an address on Pushkinskaya Street, on the appointed day and hour I showed up at the apartment of Maria Alexandrovna Nikitina, my aunt friends. Entering the small dining room, I found everyone already gathered at the oval table, set for tea, with 6-7 young interesting ladies sitting. I knew two of them by sight (they met in the halls of the Winter Palace, where it was organized by Alexandra Fedorovna. sewing linen for the wounded). They were all in the same circle and were talking animatedly among themselves. Having made a general bow in English, I sat down next to the hostess at the samovar and talked with her.

Suddenly there was a sort of general sigh - Ah! I looked up and saw in the doors located at opposite side, from where I entered, a powerful figure - the first impression - a gypsy. The tall, powerful figure was clad in a white Russian shirt with embroidery on the collar and fastener, a twisted belt with tassels, untucked black trousers and Russian boots. But there was nothing Russian about him. Black thick hair, a large black beard, a dark face with predatory nostrils of the nose and some kind of ironic, mocking smile on the lips - the face is certainly impressive, but somehow unpleasant. The first thing that attracted attention was his eyes: black, red-hot, they burned, piercing right through, and his gaze on you was simply felt physically, it was impossible to remain calm. It seems to me that he really had a hypnotic power that subjugated him when he wanted it...

Everyone here was familiar to him, vying with each other to please and attract attention. He sat down at the table cheekily, addressed everyone by name and “you,” spoke catchily, sometimes vulgarly and rudely, called them to him, sat them on his knees, felt them, stroked them, patted them on soft places, and everyone “happy” was thrilled with pleasure. ! It was disgusting and offensive to watch for women who were humiliated, who lost both their feminine dignity and family honor. I felt the blood rushing to my face, I wanted to scream, punch, do something. I was sitting almost opposite the “distinguished guest”; he perfectly sensed my condition and, laughing mockingly, each time after the next attack he stubbornly stuck his eyes into me. I was a new object unknown to him...

Impudently addressing someone present, he said: “Do you see? Who embroidered the shirt? Sashka! (meaning Empress Alexandra Feodorovna). No decent man would ever reveal the secrets of a woman's feelings. My eyes grew dark from tension, and Rasputin’s gaze unbearably drilled and drilled. I moved closer to the hostess, trying to hide behind the samovar. Maria Alexandrovna looked at me with alarm...

“Mashenka,” a voice said, “do you want some jam?” Come to me." Mashenka hurriedly jumps up and hurries to the place of summoning. Rasputin crosses his legs, takes a spoonful of jam and knocks it over the toe of his boot. “Lick it,” the voice sounds commanding, she kneels down and, bowing her head, licks the jam... I couldn’t stand it anymore. Squeezing the hostess’s hand, she jumped up and ran out into the hallway. I don’t remember how I put on my hat or how I ran along Nevsky. I came to my senses at the Admiralty, I had to go home to Petrogradskaya. She roared at midnight and asked never to ask me what I saw, and neither with my mother nor with my aunt did I remember this hour, nor did I see Maria Alexandrovna Nikitina. Since then, I could not calmly hear the name Rasputin and lost all respect for our “secular” ladies. Once, while visiting De-Lazari, I answered the phone and heard the voice of this scoundrel. But I immediately said that I know who is talking, and therefore I don’t want to talk..."

The Provisional Government conducted a special investigation into the Rasputin case. According to one of the participants in this investigation, V. M. Rudnev, sent by order of Kerensky to the “Extraordinary Investigative Commission to investigate the abuses of former ministers, chief managers and other senior officials” and who was then a comrade prosecutor of the Yekaterinoslav District Court: “the richest material for coverage his personality from this side turned out to be in the data of that very secret surveillance of him, which was carried out by the security department; at the same time, it turned out that Rasputin’s amorous adventures did not go beyond the framework of nightly orgies with girls of easy virtue and chansonette singers, and also sometimes with some of his own. petitioners."

Daughter Matryona in her book “Rasputin. Why?" wrote:

"...that, with all the saturated life, the father never abused his power and ability to influence women in a carnal sense. However, one must understand that this part of the relationship was of particular interest to the father’s ill-wishers. I note that they received some real food for their tales ".

Rasputin's daughter Matryona emigrated to France after the revolution and subsequently moved to the USA.

The remaining members of Rasputin's family were subjected to repression by the Soviet authorities.

In 1922, his widow Praskovya Fedorovna, son Dmitry and daughter Varvara were deprived of voting rights as “malicious elements.” Even earlier, in 1920, Dmitry Grigorievich’s house and entire peasant farm were nationalized.

In the 1930s, all three were arrested by the NKVD, and their trace was lost in the special settlements of the Tyumen North.